Fertilization and cellular remodelling – from egg to embryo

Life of sexually reproducing organisms starts with the fusion of two highly specialized cells, the egg and the sperm, to form a single cell, the zygote. This totipotent cell gives rise to all cells of the future organism. Triggered by two key discoveries, namely that i) translation is more wide-spread than anticipated and often occurs outside of known, annotated genes, and ii) that some of these newly identified translated regions can encode previously missed, essential small proteins (Pauli & Valen et al., 2012; Chew et al., 2013; Pauli et al., 2014; Chew et al., 2016; Cabrera-Quio & Herberg, Pauli, 2016), our main focus over the past years has been on the functional characterization of novel, essential short proteins during embryogenesis. This research has culminated in the identification of Toddler/Apela (Pauli et al., 2014) and Bouncer (Herberg et al., 2018).

Our recent discovery of Bouncer as a species-specific fertilization factor in fish has established fertilization as a new, exciting research direction in my lab. In addition, stemming from our general interest in regulatory principles that govern the large-scale transformation of the egg cytoplasm into the cytoplasm of metabolically active, embryonic cells, we have initiated mechanistic work on mRNA and translational regulation during the oocyte-to-embryo transition. The long-term vision of the Pauli lab is to unravel new concepts and molecular principles governing the oocyte-to-embryo transition.

Our current research is centered around the following topics:

- Fertilization: How is fertilization regulated? We are specifically interested in identifying new molecular players and gain mechanistic insights into sperm-egg interaction and fusion.

- Translational regulation: We are interested in investigating translational regulation during embryogenesis.

- Toddler: How does the short, secreted protein Toddler/Apela regulate gastrulation movements?

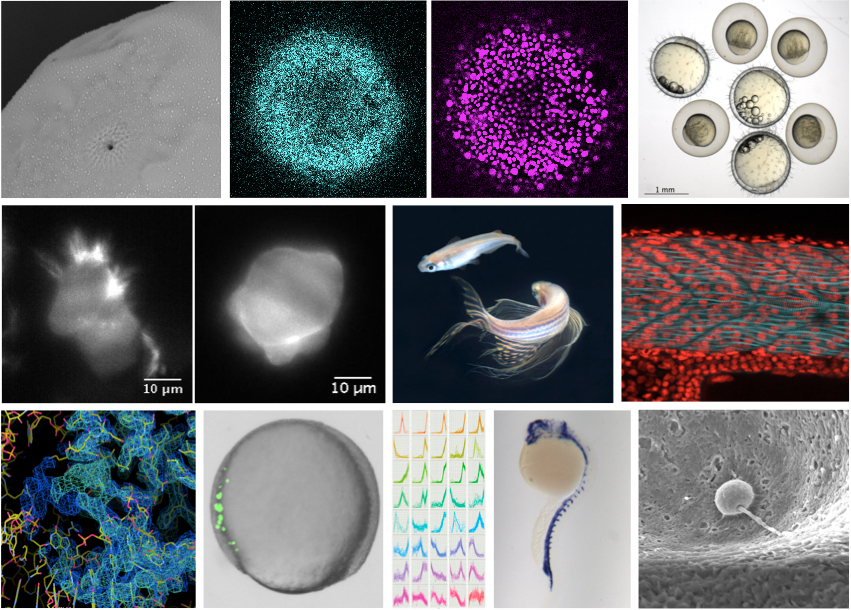

To address these questions, we are mainly using zebrafish embryos since they are a powerful model of vertebrate embryogenesis. We combine various approaches, ranging from genetics, molecular and cell biology, biochemistry and structural biology to live cell imaging, genomics and evolutionary analyses.

Discovery of Bouncer as an essential vertebrate fertilization factor

Fertilization faces two main challenges: On the one hand, sperm-egg fusion has to be highly efficient. On the other hand, it has to be species-specific. Mechanisms that limit fertilization to conspecific sperm are of particular importance for the perpetuation of species that use external fertilization. However, despite decades of research, it is still unclear how these two requirements are met at the molecular level since none of the currently known proteins essential for sperm-egg interaction in vertebrates, CD9 (Kaji et al., 2000; Miyado et al., 2000; Le Naour et al., 2000), IZUMO1 (Inoue et al., 2005) and JUNO (Bianchi et al., 2014), confer species-specificity to fertilization.

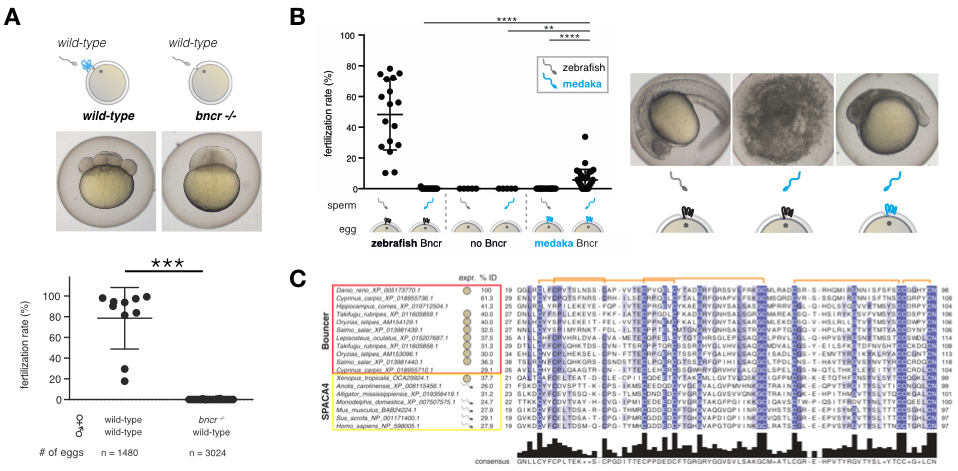

Our recent discovery of the short, un-annotated Ly6/uPAR-type protein Bouncer as a species-specific fertilization factor in zebrafish (Figure 1) (Herberg et al., 2018) comprises an important milestone in the field of reproductive biology. We originally identified Bouncer as an unannotated, putative protein-coding region in a screen for novel protein-coding genes expressed during zebrafish embryogenesis (Pauli et al., 2014). Female zebrafish lacking Bouncer (bncr-/-) are sterile (Figure 1A) since sperm can no longer bind to and enter the egg. Remarkably, further analysis revealed that Bouncer is not only required for sperm-egg interaction, but provides species specificity in fertilization in the case of zebrafish and medaka, two fish species that have diverged more than 200 million years ago and cannot normally cross-fertilize. By replacing zebrafish Bouncer with the evolutionarily distant medaka Bouncer in the zebrafish egg, we found that changing this single factor prevents zebrafish sperm from entering but instead allows medaka sperm to fertilize the zebrafish egg (Figure 1B). Thus, Bouncer acts as the gate-keeper of the egg, enabling conspecific sperm to enter while keeping hetero-specific sperm out (Herberg et al., 2018). Interestingly, Bouncer’s mammalian homolog, SPACA4/SAMP14, is expressed exclusively in the male germline in vertebrates with internal fertilization (Figure 1C), raising the possibility that our findings in fish can have direct relevance to mammalian biology.